Article 8 (j) and related provisions of the Convention. This working group is open to all Parties, Indigenous and local communities representatives.

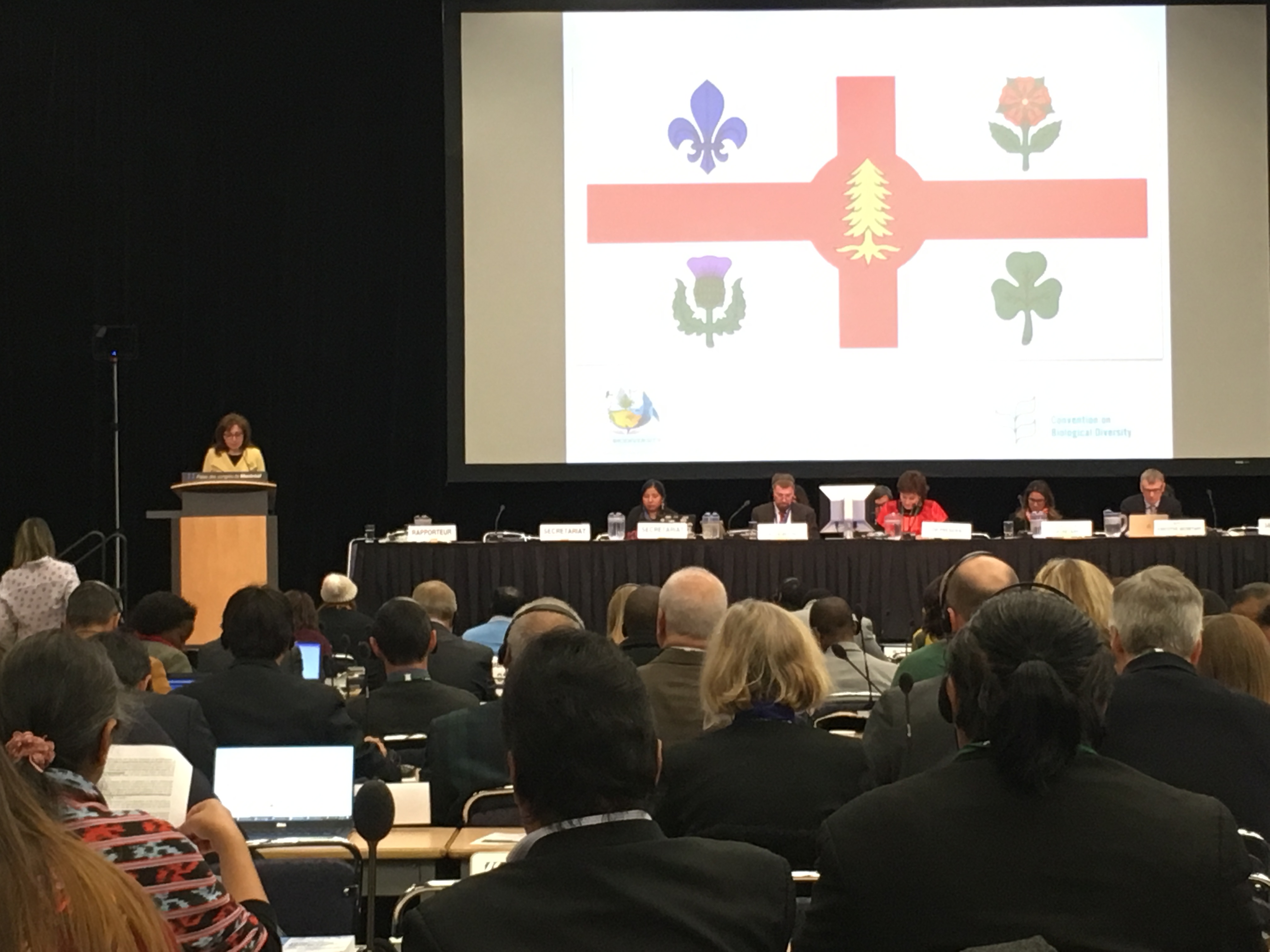

The 10th Meeting of the Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group for Article 8(j): Traditional Knowledge of Indigenous Peoples & Local Communities was held in the Palais des congrès de Montréal. The Plenary hall was filled with over 500 delegates from countries all over the world, and NGO’s, students, Indigenous groups, lawyers, and scientists.

We gathered here in Montréal from December 12th to 16th, 2017 to discuss issues revolving around the use of Traditional Knowledge (TK) in the context of biodiversity. It is clear from the plenary sessions and series of side events that culture and biodiversity are undeniably linked.

We gathered here in Montréal from December 12th to 16th, 2017 to discuss issues revolving around the use of Traditional Knowledge (TK) in the context of biodiversity. It is clear from the plenary sessions and series of side events that culture and biodiversity are undeniably linked.

Article 8 refers to In-situ Conservation: “(j) Subject to its national legislation, respect, preserve and maintain knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and promote their wider application with the approval and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilization of such knowledge, innovations and practices;”

Day 1 Voluntary Guidelines The review of comments and suggestions by various countries for implementation of guidelines and other documents provided perspective on what countries are concerned about in terms of the use of TK. The delegates representing Japan had concerns about the copyright of TK. Guidelines have been drafted in order to facilitate appropriate use of TK with prior, informed consent. Brazil was concerned about the equitable sharing of benefits from the use of biodiversity and availability of TK. Guidance and support will be necessary for future recognition of rights to facilitate the access and use of TK. It was found that the adoption of the guidelines needs improvement, as this is not simply a symbolic document. It is necessary to govern the use of TK, to ensure prior, informed consent is achieved. Argentina voiced their concerns about the time frames for the repatriation of knowledge. These guidelines must also be geared towards businesses and industry who are most likely to be using the information from TK. Colombia has been working together with Indigenous Peoples to build a framework information system for the wellbeing of people in the Amazon. This intercultural dialogue focuses on moving forward with the integration of people and nature. However they did voice concerns about needing more clarity for gender specific roles of preserving biodiversity. Ecuador has also made progress for the repatriation of TK. In 2016, a law was passed in Ecuador for the legal protective measured of TK. Moving forward, they aim to create equal ground for Indigenous peoples and for the potential use of TK to have distinction between the user and the holder of the information. The rights of the TK holders must be monitored. Cambodia is working on a capacity building program at National and Subnational levels in order to use biodiversity sustainably. Cambodia has 4 million hectares of evergreen forest that is managed through a land use system of cultivation and animal husbandry. The repatriation of TK is crucial for maintaining biodiversity in their evergreen forests so people and nature can harmonize. Morocco is strengthening TK and cultural heritage in relation to biodiversity. This synergy aims to influence the guidelines and streamline values amongst parties and organizations. Switzerland shares similar concerns with Japan regarding copyright infringements of TK. Other purposes for TK besides museums, schools, and other institutions that collect TK may have the potential for copyright issues. Switzerland believes, however, that TK is beneficial, but what are the obligations of the holder of TK? Bolivia strongly believes that TK preservation is of the highest importance, and adopting the voluntary guidelines will ensure consent and for the fair and equitable sharing of benefits obtained from the use of biodiversity and TK. Although the guidelines are important, they also require improvement so they are more clear. India is pleased with the progress made my the guidelines but requires more support in order to successfully protect TK, TK holder’s rights, and biodiversity. China struggles with the lack of capacity and structure to successfully repatriate TK. Korea also lacks capacity and provisions, and requires strategies to best return lost knowledge to original holders. These guidelines for the sustainable use of biodiversity, developments, strategies and repatriation of Indigenous Knowledge can be found on the UN CBD website under CBD/WG8J/10/2. Glossary The glossary is an inclusive, living document which aims to provide understanding of key terms in the context of Article 8(j). The glossary, similarly to the voluntary guidelines, were open for comment by the countries present at the conference. It was determined through discussion that there must be mechanisms in place for periodic review of the terms in the glossary and infringement on rights of TK must not be compromised. Terms in the glossary must be used solely for the purpose of the Convention. It was acknowledged by several countries that different cultures use the same word differently, and are subject to legislation or customary laws in their distinct nationalities. The glossary can be found on the UN CBD website under CBD/WG8J/10/3. Resource Mobilization The methodological guidance for identification, monitoring, and assessment of information from contributors of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities is necessary in order to maintain TK and biodiversity. Information regarding these strategies can be found on the CBD website under CBD/WG8J/10/5.

Side Event: IPBES Intercultural Framework & Perspective

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is an independent intergovernmental body that was established in 2012. It provides policy makers with objective, scientific assessments and knowledge regarding biodiversity.

The main objective of IPBES is to strengthen knowledge foundations for better policy through science for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. This mission is achieved through assessments, policy support, building capacity an knowledge, and community outreach.

The side event provided information about IPBES and their work on the Global Biodiversity Strategy & Outlook. This report aims to provide a comprehensive assessment to state the knowledge of the past, present and future, with evaluation, incentives, goals and assessments. The knowledge is inclusive of Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge, with participatory mechanisms in place to enhance strategic partnerships and ensure prior, informed consent. The report is addressing the pressures, conflicts and fast-paced rate of change that is occurring on the global scale. The findings from this report are to be presented in 2019.

Side Event: IPBES Intercultural Framework & Perspective

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is an independent intergovernmental body that was established in 2012. It provides policy makers with objective, scientific assessments and knowledge regarding biodiversity.

The main objective of IPBES is to strengthen knowledge foundations for better policy through science for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. This mission is achieved through assessments, policy support, building capacity an knowledge, and community outreach.

The side event provided information about IPBES and their work on the Global Biodiversity Strategy & Outlook. This report aims to provide a comprehensive assessment to state the knowledge of the past, present and future, with evaluation, incentives, goals and assessments. The knowledge is inclusive of Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge, with participatory mechanisms in place to enhance strategic partnerships and ensure prior, informed consent. The report is addressing the pressures, conflicts and fast-paced rate of change that is occurring on the global scale. The findings from this report are to be presented in 2019.

Traditional Knowledge is locally based, but globally relevant.Joji Carino, with the Forests Peoples Programme, represents Indigenous Peoples within IPBES and understands how crucial TK is to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity. Centres of Distinction is a tool IPBES, Indigenous groups, and organizations alike are hoping to implement to create a network for effective engagement. This will facilitate specific workshops and reports for regional assessments. It is not easy to aggregate and synthesize knowledge at a regional scale, let alone globally. Indigenous groups rely on culture and experience to shape unique ways of actualizing the Aichi Targets. Working solely with scientific methodologies is challenging for Indigenous peoples, but Joji is hoping that Indigenous groups can utilize new technologies for the revitalization of TEK. This will need specific indicators for Indigenous groups, with earlier dialogues to help shape the questions we wish to answer. The team is working towards synthesizing scientific methodology and TEK by providing workshops on indicators, sociocultural preferences, consultation, land use, and regional and local perspectives. The aim of IPBES is to gather as much information as possible to add to the knowledge base. In order to do this, an online forum has been created for easier inputs and collaborations, however the consent of the knowledge holder must be given for the information to be used so the rights of Indigenous peoples are not infringed upon. For more info on IPBES: Twitter: @IPBES youtube.com/ipbeschannel facebook.com/IPBES

Day 2 Day 2 of the Convention began with discussing resource mobilization and assessing the contribution of collective actions of Indigenous Peoples and local communities – safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms. The Subsidiary body supports the creation of this document, but suggests looking deeper into options and mechanisms for further participation. Delegates from various countries spoke about their contributions and additions to the document. There were still concerns about the burden of proof and benefit sharing from TK and use of biodiversity. The Women’s Group spoke about ecosystem based management approaches and how they are often organized by women. The role of gender appears several times throughout the CDB and Aichi Targets, but the Environmental Defenders group voiced that many Indigenous peoples and women (1 out of 4) are dying on the front lines of protecting the environment. These groups believe that human rights must be on the forefront of dealing with these issues, and not enough is being done to prevent the deaths of Indigenous Peoples and women. Side Event: Subnational Governments for Maintaining Biodiversity into Energy & Mining Sectors, & Health This side event consisted of presentations from various countries involved with the programme to mainstream biodiversity into industrial sectors. Accomplished on the subnational level, these participants produced practical actions to achieve their goals. Regions for Biodiversity Learning Platform – this platform is a global community of 10 proactive regional governments working together to conserve and protect biodiversity, encourage healthy ecosystems, and promote sustainable livelihoods for their citizens. The regional governments are working toward subnational implementation of the CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and achieving the Aichi Biodiversity Targets by designing and implementing policies and best practices intended to drive progress, promote innovation, and contribute to advancing the global biodiversity agenda. More info: http://www.nrg4sd.org/biodiversity/r4blp/ Quebec presented their achievements on harmonizing biodiversity with their extensive road networks by building under and over passes, installing fencing, planting native species for erosion and stability control, and enacting laws to protect wetlands. In Aichi, Japan, their goal is to mainstream biodiversity into their manufacturing and processing industries, specifically automotive and airplane. Their efforts began by outreach, education, and communication. In 2014 they had a UNSECO site established, as well as a World Expo. There has been effort from business sectors, specifically Toyota, which aims to eliminate C02 by 2050. Ontario’s focus was on health. Ecosystem functions provide healthy food, clean water, nutrition, and medicines. The Ontario Government has been active in supporting these efforts, and created a Sectoral Response Plan. They aim to increase public awareness through campaigns and working groups to educate the public on ecosystem benefits, green spaces, and promoting science and nature. A children’s outdoor charter was created to get kids connected with nature. There is also a monitoring system and climate change adaption tool kit online and available to the public. Mexico spoke about the mining sector, specifically a 30+ year old mine covering 200 hectares in Veracruz. A remediation plan has been developed with the Institute of Ecology with local forest technicians. Their 3-stage plan encompasses strategies for biodiversity, as the ground is infertile and ver demanding to repair. By beginning with grass seed, they were able to stabilize soil, plant small bushes which attracted birds and small mammals, which accelerates the process of reclamation. They now have larger tree species growing in the area. The integration of biodiversity and industry prompted me to write a short article for ECO, the opinion-based journal published by the CBD Alliance. It can be found here: ECO-55-4

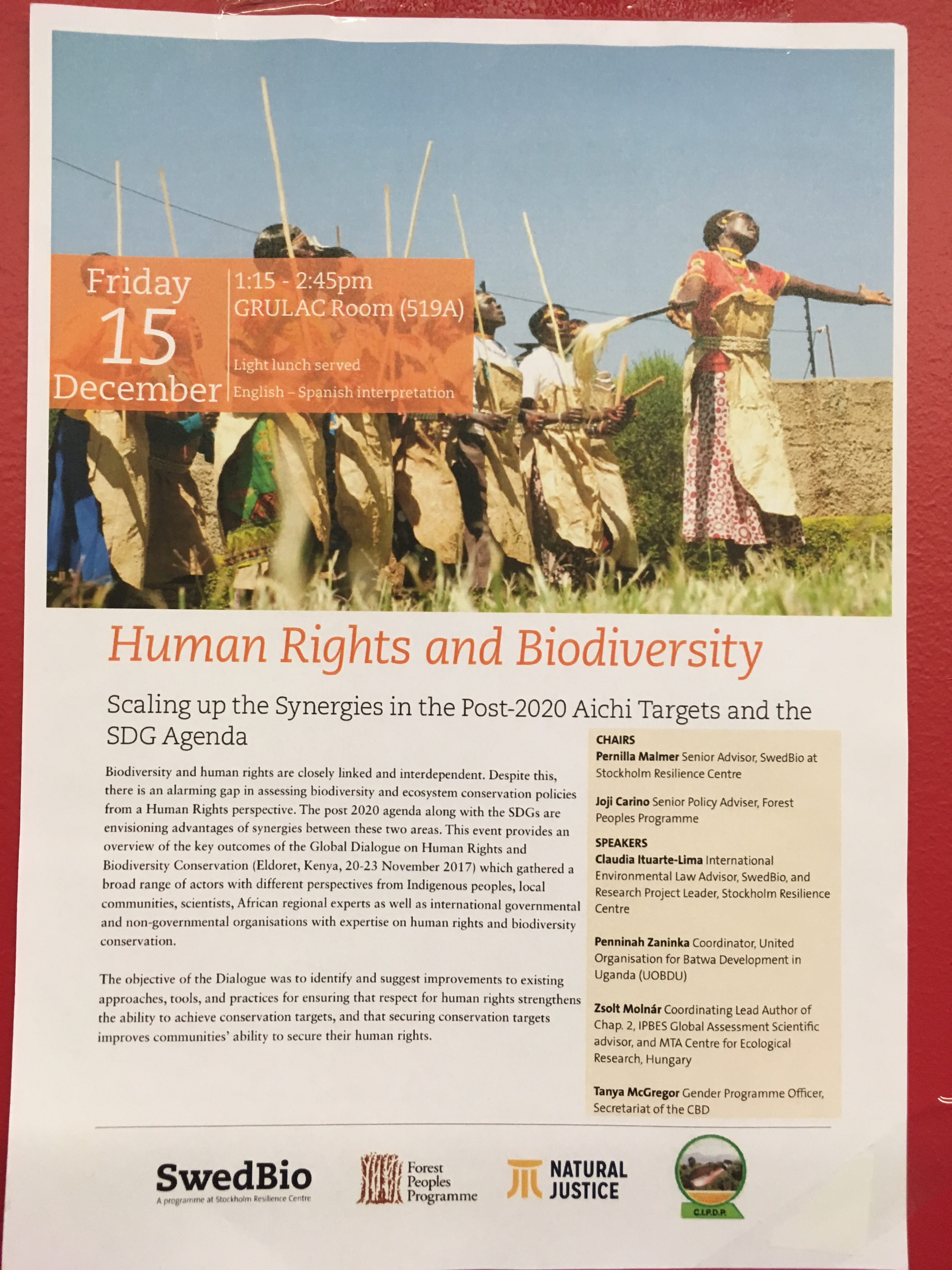

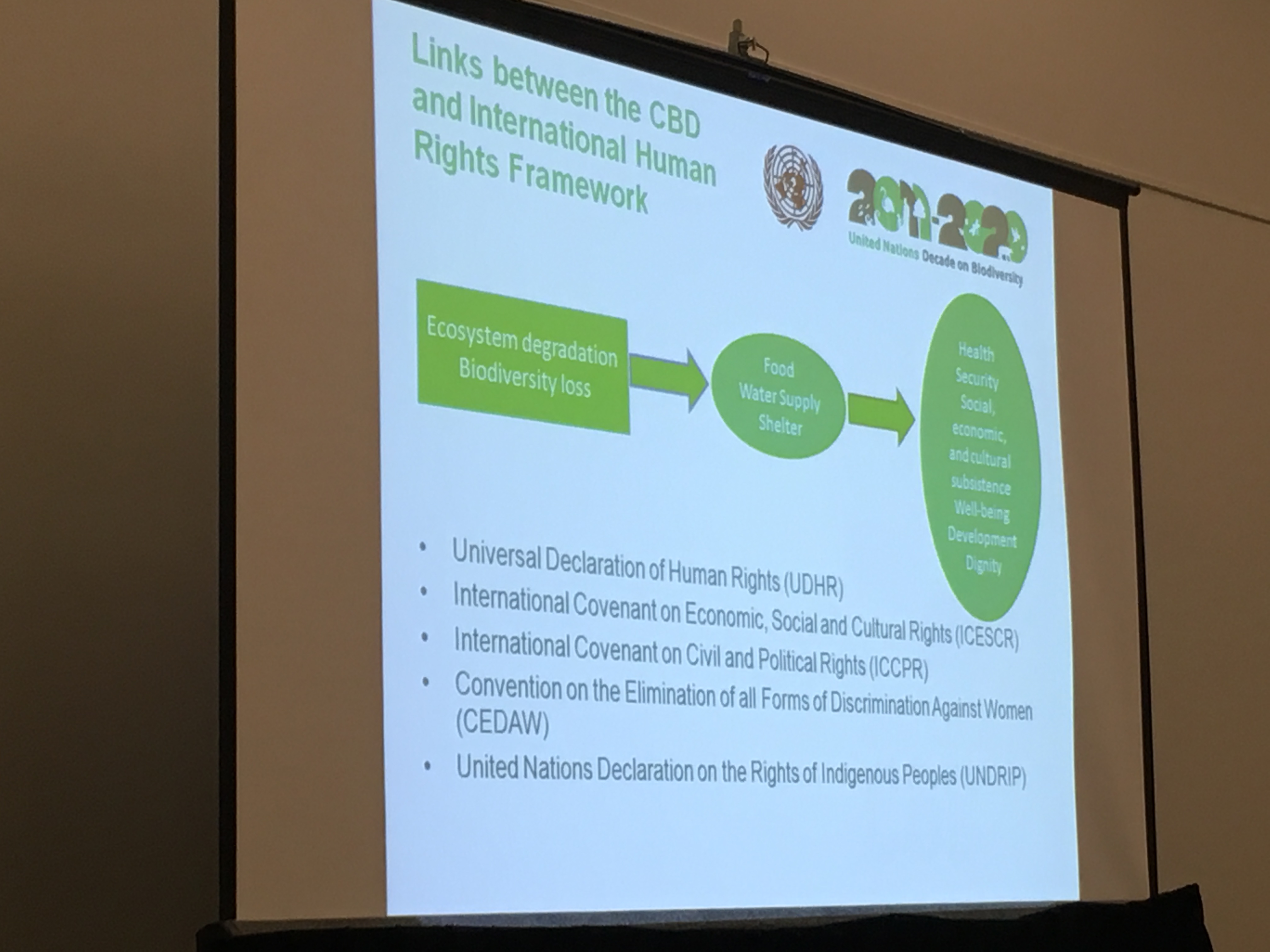

Day 3 Traditional Back in the Plenary sessions, there was an interesting discussion between countries as to what the word “traditional” means. Argentina voiced their opinion: that there are two components to “traditional”, time and relation. Difficulties can arise if nations have preexisting legislation that defines “traditional”, such as in customary law. It was agreed that for the CBD, the context of “traditional” was in context of biodiversity use and conservation. Thematic Areas & other Cross-cutting Issues This discussion was meant to be focused on thematic areas and cross-cutting issues, in the context of implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the sustainable use of biodiversity and conservation for the 2030 Agenda, but unfortunately Parties said they did not have adequate time with these documents and would like to discuss this further at the 11th Meeting. The documents regarding this topic can be found on the CBD website under CBD/WG8J/10/10. Side Event: Conservation & Human Rights This side event was hosted by Joji Carino with the Forest Peoples Programme (FPP), and Pernilla Maimer with Swedbio. Historically, there has been a contemporary divide between conservation and human rights. The 2030 Agenda aims to achieve biodiversity targets while respecting human rights.

There are many partners involved in this goal, including Natural Justice, Human Rights Council, IUCN, FPP, UNESCO, and Swedbio, among others. A conceptual framework of people and linkages to build capacity to achieve these goals is required, but the right questions must be asked. This means opening a dialogue early to ensure the right indicators are identified by Indigenous Peoples themselves. Some questions include:

There are many partners involved in this goal, including Natural Justice, Human Rights Council, IUCN, FPP, UNESCO, and Swedbio, among others. A conceptual framework of people and linkages to build capacity to achieve these goals is required, but the right questions must be asked. This means opening a dialogue early to ensure the right indicators are identified by Indigenous Peoples themselves. Some questions include:

- Why do conflicts arise?

- How can we avoid these conflicts?

- When conflict do arise, how is it efficiently and equitability resolved?

It has been observed that Indigenous practices are not negatively affecting biodiversity, and that they are sustainable. The issues come from the hard laws such as constitutions that restrict action towards biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Women’s rights are also relevant in this context, as many women are responsible for gathering resources such as water. If women don’t have access to water, entire communities will suffer. The displacement of communities in the name of conservation is an issue, and the narrative of forest peoples must be questioned. These issues are directly addressed in the Sustainable Development Goal 16 – to identify laws, policies and practices that need to changed.

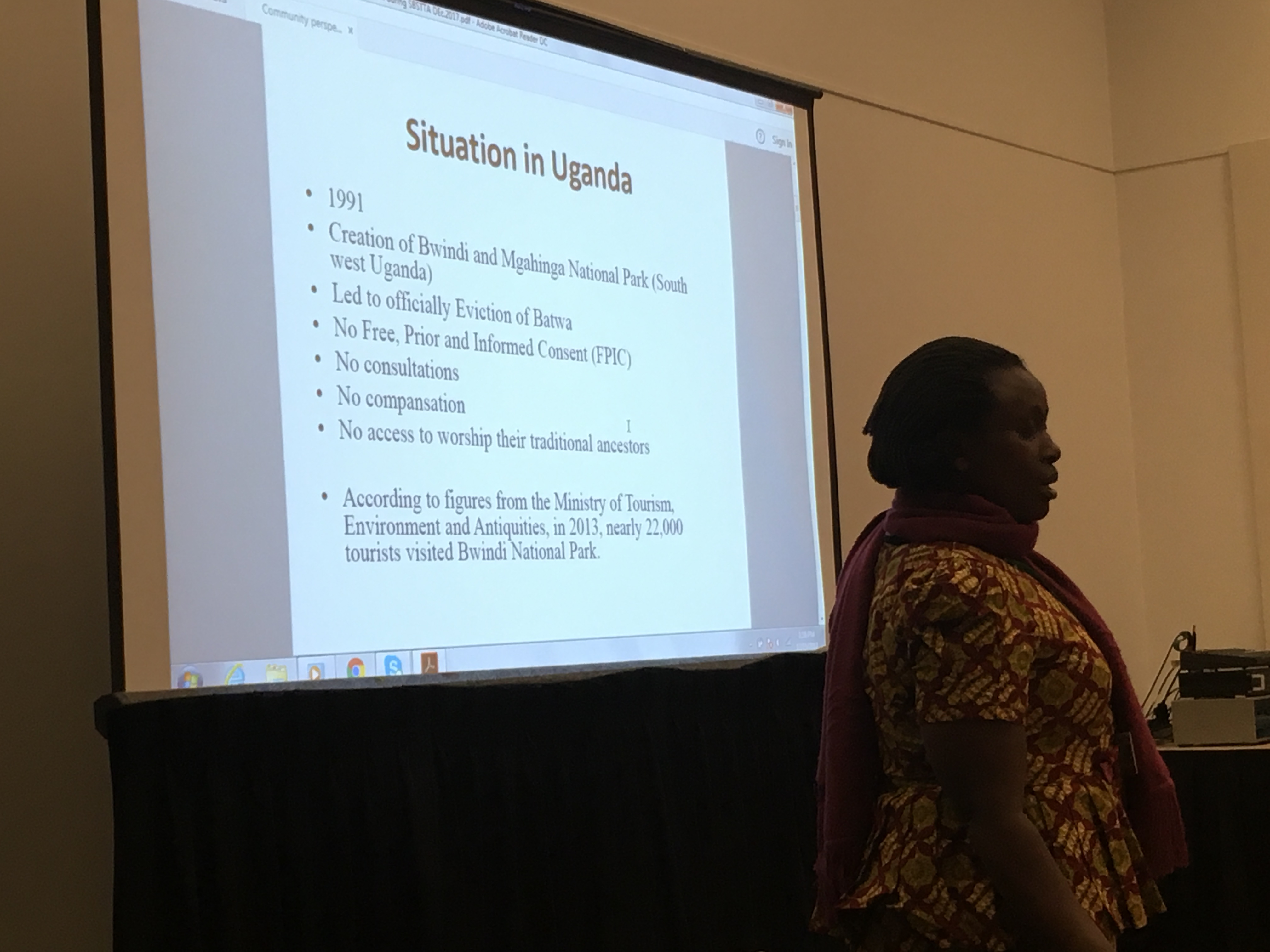

The third speaker at the side event was Penninah Zaninka from Uganda. Her presentation was on the community perspective of human rights and conservation in Uganda. In 1991, people in Uganda were officially evicted from their homes and villages for the creation of parks. This displacement and removal of people had been ongoing since the 1930’s, and is regulated by patrolmen with guns to restrict access to traditional lands. The people were no longer able to harvest plants for medicines, had no access to food or any traditional uses of the land.

It has been observed that Indigenous practices are not negatively affecting biodiversity, and that they are sustainable. The issues come from the hard laws such as constitutions that restrict action towards biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Women’s rights are also relevant in this context, as many women are responsible for gathering resources such as water. If women don’t have access to water, entire communities will suffer. The displacement of communities in the name of conservation is an issue, and the narrative of forest peoples must be questioned. These issues are directly addressed in the Sustainable Development Goal 16 – to identify laws, policies and practices that need to changed.

The third speaker at the side event was Penninah Zaninka from Uganda. Her presentation was on the community perspective of human rights and conservation in Uganda. In 1991, people in Uganda were officially evicted from their homes and villages for the creation of parks. This displacement and removal of people had been ongoing since the 1930’s, and is regulated by patrolmen with guns to restrict access to traditional lands. The people were no longer able to harvest plants for medicines, had no access to food or any traditional uses of the land.

In the name of conservation, the park, Bwindi National Park, was designated a UNESCO heritage site, with no compensation to people who were evicted. This created social issues, affected livelihoods, prevented people from access to education and health care, and these people still have no income. The Uganda Human Rights Commission has been contacted, and a case has been waiting to see Constitutional Court for 5 years.

Meanwhile, the utilization of new technology has allowed the Indigenous peoples of Uganda to map their traditional territories. Traditional Knowledge from elders has contributed to the successful mapping of the lands they were once evicted from. This TK also allows for the sustainable management of forests. With the use of TK and new technology, the people of Uganda hope to regain access to their traditional territories to contribute to the sustainable management of forests and to harvest natural products to sustain their own way of life.

The fourth and final speaker of this side event was Zsolt Molnar, an Ethnoecologist from Hungary. His research focused on the Ogiek Peoples in Kenya. As a scientist working for IPBES, Molnar concluded through his research and experiences that human rights should come first, and conservation of biodiversity second. When people are focused on the environment, human rights can be forgotten. Indigenous peoples living on the land help to shape the cultural landscape, and their rights and knowledge is equally as important as biodiversity.

His research takes place in Kenya in the Mt. Elgon region, where Indigenous peoples have lived for generations in what is now protected forests. The government of Kenya changed the natural species of these forests to exotic species for plantations, called the Shamba system. It has been found that these plantations are not functioning properly, has displaced the Ogiek People, has degraded vegetation and opened up the canopy of the forest, and has consequently lead to the overuse of the landscape, primarily from grazing.

The Ogiek People were stewards of the forests, but were forced up land to Mt. Elgon, where forests don’t grow. When traditionally living on the land, the Ogiek People don’t cut live trees down. Plantations are not run the same way, and land degradation has been rapid. The Ogiek People have been fighting for their rights, publishing bylaws, using mapping technologies, and creating dialogues. After 26 years of fighting, the African Courts System has granted them access to these “protected forests” that have been converted into plantations. They have proven to the African government that they are responsible, and have developed protocols for using the forest.

In the name of conservation, the park, Bwindi National Park, was designated a UNESCO heritage site, with no compensation to people who were evicted. This created social issues, affected livelihoods, prevented people from access to education and health care, and these people still have no income. The Uganda Human Rights Commission has been contacted, and a case has been waiting to see Constitutional Court for 5 years.

Meanwhile, the utilization of new technology has allowed the Indigenous peoples of Uganda to map their traditional territories. Traditional Knowledge from elders has contributed to the successful mapping of the lands they were once evicted from. This TK also allows for the sustainable management of forests. With the use of TK and new technology, the people of Uganda hope to regain access to their traditional territories to contribute to the sustainable management of forests and to harvest natural products to sustain their own way of life.

The fourth and final speaker of this side event was Zsolt Molnar, an Ethnoecologist from Hungary. His research focused on the Ogiek Peoples in Kenya. As a scientist working for IPBES, Molnar concluded through his research and experiences that human rights should come first, and conservation of biodiversity second. When people are focused on the environment, human rights can be forgotten. Indigenous peoples living on the land help to shape the cultural landscape, and their rights and knowledge is equally as important as biodiversity.

His research takes place in Kenya in the Mt. Elgon region, where Indigenous peoples have lived for generations in what is now protected forests. The government of Kenya changed the natural species of these forests to exotic species for plantations, called the Shamba system. It has been found that these plantations are not functioning properly, has displaced the Ogiek People, has degraded vegetation and opened up the canopy of the forest, and has consequently lead to the overuse of the landscape, primarily from grazing.

The Ogiek People were stewards of the forests, but were forced up land to Mt. Elgon, where forests don’t grow. When traditionally living on the land, the Ogiek People don’t cut live trees down. Plantations are not run the same way, and land degradation has been rapid. The Ogiek People have been fighting for their rights, publishing bylaws, using mapping technologies, and creating dialogues. After 26 years of fighting, the African Courts System has granted them access to these “protected forests” that have been converted into plantations. They have proven to the African government that they are responsible, and have developed protocols for using the forest.

Day 4 The final day of the Plenary sessions began with the adoptions of the CRP’s (conference room papers) that had been discussed in prior sessions. CRP 6: Ways and instruments for achieving full implementation of Article 8(j) and provisions related to Indigenous Peoples and local communities was adopted. This CRP is meant to provide coherence and coordination between Parties for the successful implementation of Article 8(j). An online forum will be established for governments, organizations, Indigenous groups, and other associated members to contribute to the post 2020 framework. An exchange of views, pros and cons of current management, and contribution of knowledge will assist the development of the post 2020 framework. The adoption of CRPs was followed by presentations by 4 board members. The first was Yoko Wantanabe, who discussed the contribution of Traditional Knowledge to the SDGs. The global environment is affected by climate change, land degradation, pollution, and other issues that are being tackled in the SDGs. The underlying fundamental issue is that we use land for economic purposes, but with the inclusion of customary views and local knowledge, better land management and conservation of biodiversity can be achieved. Yoko continued to unpack the UN Development Plan and the UN Development System, and how they tie into nature-based solutions with different development pathways in order to achieve goals. A bottom up approach is required, with local support for communities and multi stakeholder approaches to ensure innovative actions on the ground. So far, the UN DP has served 125 countries over 25 years with over 20,000 successful projects! Among these projects, biodiversity is the largest demand and has the biggest portfolio. Over 650 projects in 110 countries are focused on TK and Indigenous Communities. The goal of the UN DP is to show that these projects are actually working, and TK is being used to strengthen goals and targets to have a wider impact globally. There is also a focus on women and girls, as they have different needs, desires and opportunities.

The second presenter was Mrinalini Rai from Thailand with the Global Forest Coalition. Her focus is on gender equality, and the potential for gender to transform power relations in development and biodiversity. She speaks to the need for transformative change within structures and policy in place that is limiting women and girls. Only SDG 5 is for gender equality, yet many of the SDGs are still directly related to gender. There is a need for simple guidelines to acknowledge women’s rights and implement into the 2020 Action plan. Inclusive policy is the way forward to actualizing our goals!

The third speaker, Gloria Marina Apen Gonzalez from Guatemala, focused on bridging the gap between biodiversity and culture. The integration TK and scientific systems should be equal. This linkage requires models and better understanding for successful implementation. Legal and political frameworks should be developed to better manage biodiversity while respecting the rights and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples.

The fourth and final speaker was Zsolt Molnar regarding the Traditional ecological knowledge for better conservation of global biodiversity. His view as an ecologist is that we need to hybridize the knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and modern technology/science to make the best informed decisions for land management possible. The biocultural landscapes are shaped by people, and it is both an art and a science. Co-knowledge is crucial to properly management our land bases to conserve biodiversity and preserve knowledge of locals, which is forever changing, showing differences in generations.

The second presenter was Mrinalini Rai from Thailand with the Global Forest Coalition. Her focus is on gender equality, and the potential for gender to transform power relations in development and biodiversity. She speaks to the need for transformative change within structures and policy in place that is limiting women and girls. Only SDG 5 is for gender equality, yet many of the SDGs are still directly related to gender. There is a need for simple guidelines to acknowledge women’s rights and implement into the 2020 Action plan. Inclusive policy is the way forward to actualizing our goals!

The third speaker, Gloria Marina Apen Gonzalez from Guatemala, focused on bridging the gap between biodiversity and culture. The integration TK and scientific systems should be equal. This linkage requires models and better understanding for successful implementation. Legal and political frameworks should be developed to better manage biodiversity while respecting the rights and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples.

The fourth and final speaker was Zsolt Molnar regarding the Traditional ecological knowledge for better conservation of global biodiversity. His view as an ecologist is that we need to hybridize the knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and modern technology/science to make the best informed decisions for land management possible. The biocultural landscapes are shaped by people, and it is both an art and a science. Co-knowledge is crucial to properly management our land bases to conserve biodiversity and preserve knowledge of locals, which is forever changing, showing differences in generations.

Catherine and I had a wonderful time at the convention and learned a lot! It was interesting to see countries discuss issues and policy, and the side events were very informative. It was great to represent IFSA! Thank you for the opportunity to attend this event!

For any questions or more information about the event please contact Liz Wass at lizwass.ifsa@gmail.com]]>

Catherine and I had a wonderful time at the convention and learned a lot! It was interesting to see countries discuss issues and policy, and the side events were very informative. It was great to represent IFSA! Thank you for the opportunity to attend this event!

For any questions or more information about the event please contact Liz Wass at lizwass.ifsa@gmail.com]]>